Richard Petty, the Once and Future King, the most accomplished driver in the history of NASCAR— son of a race car driver, movie star, friends to presidents, the Other American Hero—had a hell of a year in 1971.

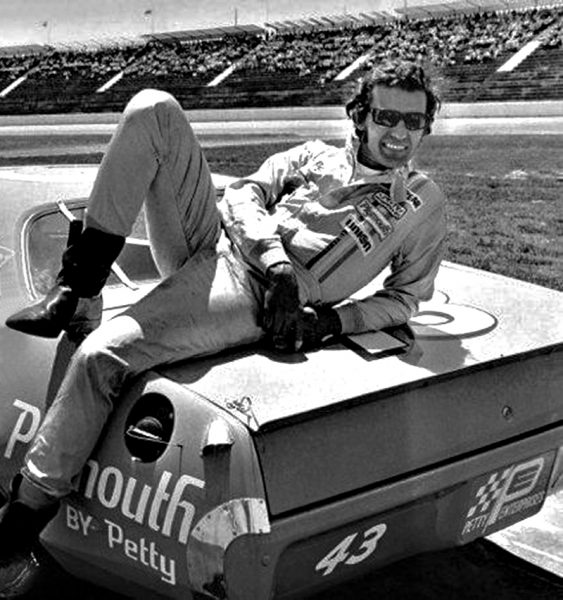

It was his “Million Dollar Year:” the year when he won 22 races, including the big one at Daytona (for the third time, no less), became the first driver to break one million dollars, and claimed his third Grand National championship—all behind the wheel of the last stock stock car in NASCAR history. It was the last year he drove for Chrysler, the last year of genuine production cars, the last year he could get away with his famous Petty Blue paint scheme—before the sponsors, famous though they might be, crept in: Colin Chapman might have been able to relate, in 1967, when he scratched out the national livery for Gold Leaf colors, British Racing Green replaced with the red, white, and gold of a cigarette company. But if America ever came close to a nationwide paint scheme, it may have well been Petty Blue, with the big white 43 painted on it.

Anyway.

Sweeping changes happen every once in a while, especially to decades-old institutions like NASCAR, cemented as they are in conservatism. But so much happened in 1971 that calling it a “time of transition” underscores the purpose. For twenty years the premiere NASCAR event had been called the Grand National Series—but before the 1971 season, the R. J. Reynolds Tobacco Company found itself booted off the airwaves and out of the magazines and swooped in with the only advertising chance it had: earning its stock-car credentials as the Winston Cup. It was the year the rules were rewritten, and the prize money went way up, and aero legends like the Superbird were restricted to engines ending at five liters—Bill France didn’t want to see the Big Three doing R&D on his tracks. Boom: no more Ford Talledega, no more Dodge Daytona. Teams were forced to either put restrictor plates and sleeved carburetors on their six-liter big-blocks, or downsize in displacement. NASCAR’s racers would become increasingly androgynous until the phrase “stock car” became tongue-in-cheek.

Petty, and Chrysler, were no stranger to rule changes. He had won his first Daytona 500 behind the wheel of a 1964 Plymouth Belvedere. Just 26 years old, and with the first 426 Hemi engines ever built, Petty took the lead from pole-sitter Paul Goldsmith and held it until the end—setting a new track record in the process.

That year, Petty said: “we was the quickest car all week long. That car, like the '64 car, was just a real fast car, and we just outrun everybody.”

A year later, NASCAR passed its most sweeping rule changes yet, banning trick, race-only tech from its stock cars—including overhead cams, high risers, and hemispherical heads.

And yet, when Petty won his second Daytona 500, the Chrysler Hemi was back. Its closest rival, Ford, took the year off. Faster and faster, Petty earned pole with an average speed of 175 mph, then led over 100 laps.

There’s nothing quite like the look of a big orange Hemi under the hood. One thing that’s a little tough to reconcile here is that single pot brake fluid reviser. Obviously, there was huge desire for throttle to the floor horsepower, but not so much for slowing down! The realities of 60’s technology.

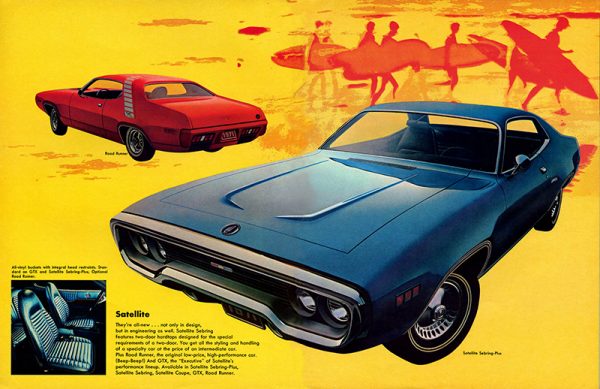

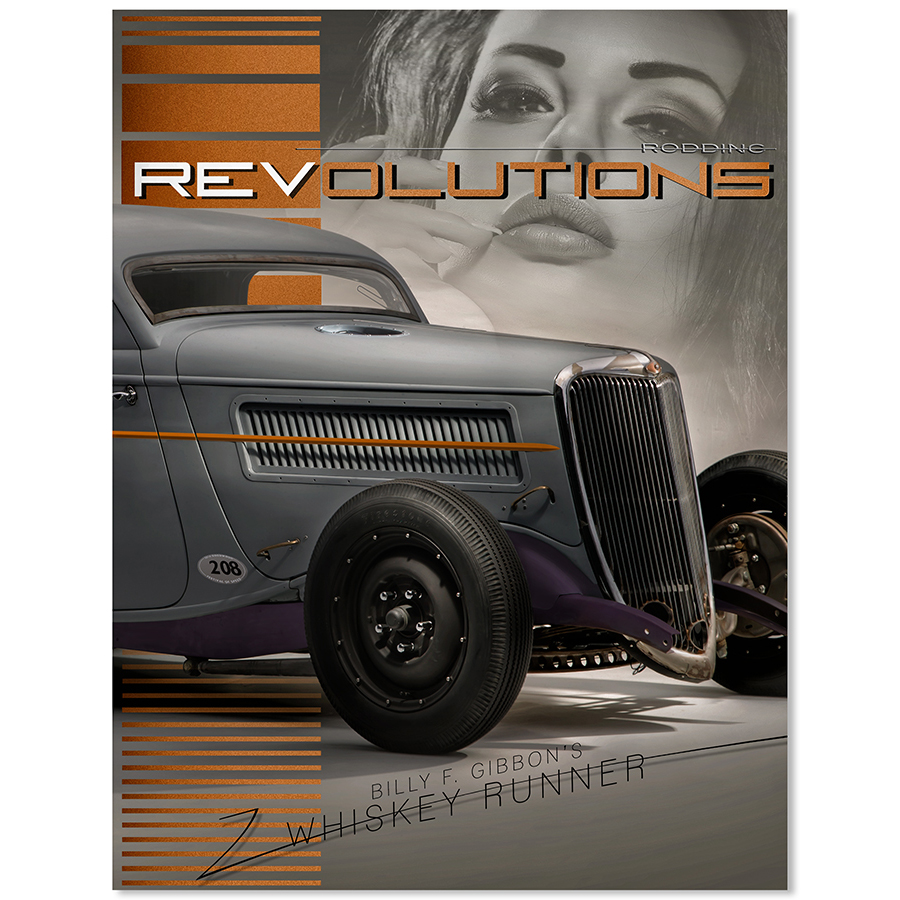

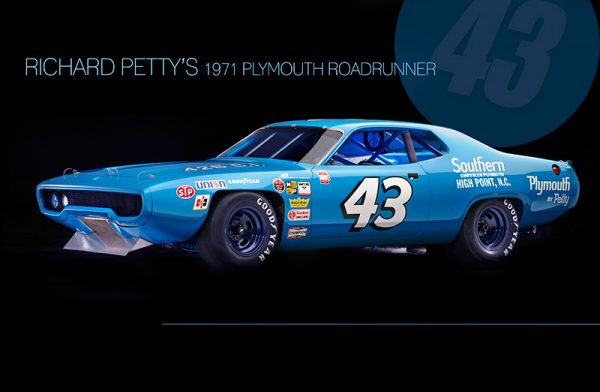

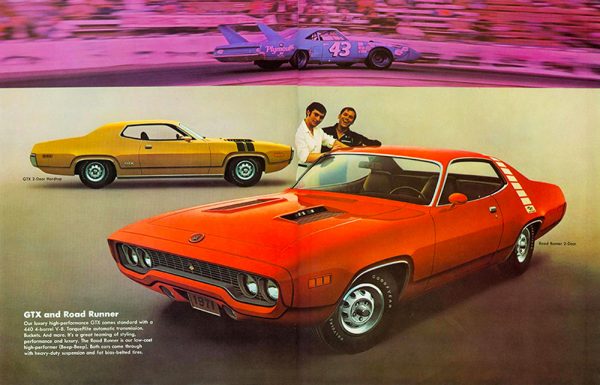

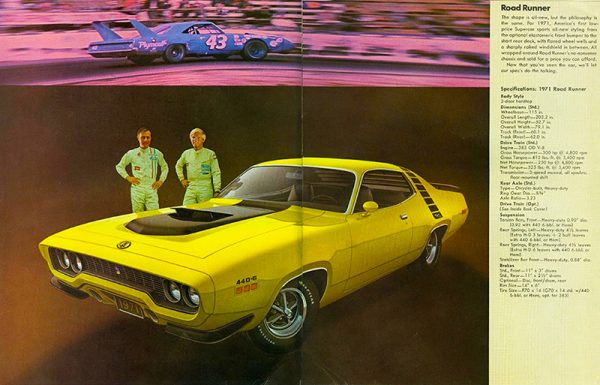

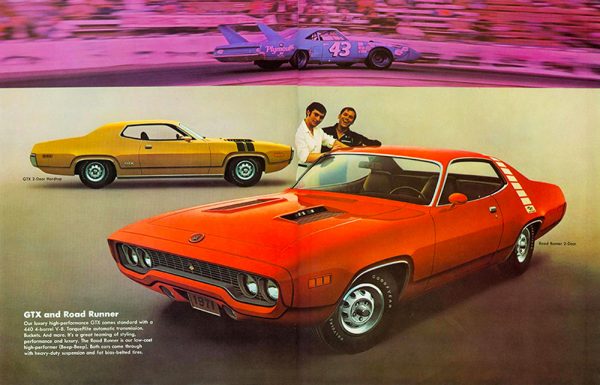

Petty was behind the wheel of the new-for-1971 Plymouth Road Runner, the second generation of the B-Bodies, the “fuselage” look that featured so many rounded edges wide and mean with four lidded eyes behind a hunk of chrome shaped like a telephone receiver. (Of course, on the race car, the chrome was gone, and the headlights were blanked out—and replaced, on the right side, by the numbers 4 and 3.)

It seemed new and shiny—and it was—but Chrysler was cutting back heavily that year. They were only fielding cars for two teams. One Dodge team, and one Plymouth. All to be prepared at Petty Enterprises in Level Cross, North Carolina. And from Petty’s legendary Superbird it was nothing close.But it still carried a 426 Hemi, the engine that carried Petty to two Daytona victories. So, some small consolation.

Petty started the 1971 season badly. Engine failure at Riverside. The new Plymouth was still under development, so he raced a year-old model at the Winston Western 500 and wound up finishing 20th.

Barely a month later, on Valentine's Day, was Daytona. The Road Runner was ready to go. Petty started in 5th place. His teammate Buddy Baker, new to Petty Enterprises, started 6th in an all-white Dodge Charger. A. J. Foyt, in a Mercury took pole with a hell of a qualifying speed at 182.744 mph.

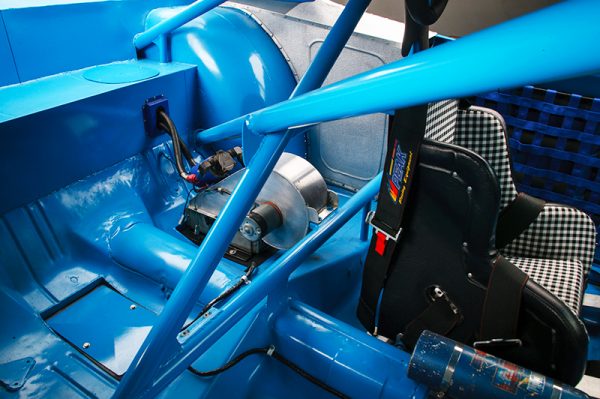

Sparse. the word to describe the driver’s office in 1971 NASCAR. Compare to a NASCAR race car from today, and it makes you wonder how any of the early icons survived. A fire bottle and a big set of gauges, along with a nice long 4 speed. And hey, it’s ‘71 so what’s wrong with a black and white plaid seat?

More than a headrest…. A sign of the times………..

And once they got underway—this wild conglomeration of fire and brimstone, these still-stock stock cars, cars these drivers were allegedly to have driven to the race, brand new and late-models, they were on the move. Foyt held his lead, while Dick Brooks and former Petty teammate Pete Hamilton battled for second. The two soon crashed. And while Brooks soldiered on to the finish, Hamilton fought valiantly to hold his car together, before ultimately succumbing to engine trouble near the end.

It was quickly Petty’s battle. Foyt was hampered by a poor pit stop, soon a lap down, and both Petty and current teammate Baker took first and second.

Petty wound up leading 69 laps. He beat Baker by ten seconds. It would be his 120th career victory, double that of the next highest-winning NASCAR driver, David Pearson. The victory pocketed him a cool $48,000—$282,000 in contemporary money—but it was only the beginning of higher and greater things.

In that Year Of Our Lord 1971, and with that Petty Blue Plymouth Road Runner, the “all-time folk hero of Southern stock car racing” (according to Chris Economaki) won 21 out of 47 races that year. He finished within the top five in 38 races. For the 1971 season, he made over $300,000. By that August, after the Dixie 500 at Atlanta International Raceway, he became the first driver to win over a million dollars in his total career, now a little over a decade old. Bask in the inflation, and embrace the mind-boggling adventure of it.

Most people don’t win 21 races in their lifetime. Most people certainly don’t win the Daytona 500 three times, much less seven. Most people don’t turn their cowboy hat into an icon, and most people don’t bring their cars to the White House to meet Richard Nixon, especially now that Nixon’s dead.

Well, you get the idea.

The glory wouldn’t last forever. At the end of the 1971 season Chrysler told Petty that they’d no longer be able to support his efforts. Petty Enterprises scrambled to find money for the 1972 season. A brush with Pepsi-Cola had dug up some cash for their two cars, but where would next year’s come from? Andy Granatelli of STP came through with a deal, and Petty was pleased—but he wanted Petty to drive a car in STP’s Fluorescent Red. Petty wasn’t willing to give up Petty Blue just yet, so Granatelli suggested both colors for the Plymouth. And thus, a new iconic livery would be associated with Petty, for the next 23 years. By 1973 puny 390-cfm carburetors were mandated for the big-blocks, by 1974 the Daytona 500 was shortened by exactly 50 miles, and by 1975 the engines were limited to 358 cubic inches—and by 1978, Petty, soldiering on with Chrysler, found the then-new Dodge Magnum that year too difficult to make competitive: “the switch to Chevrolet was the only feasible change to make under current NASCAR rules…we finally had to face the facts.”

So then, Petty represented the old school, and he wouldn’t have represented anything if he hadn’t been so good at winning.

Petty and STP, and four more Daytona victories—all through the behind the wheels of General Motors products.

But that’s another story, another day, about another car.

HEMI- Iconic, then and now. Interesting to note here is the set back, notice how far it sits behind the front axle line. Check out the original Petty logo on the fan shroud, and custom fabricated fresh air intake at the base of the cowl and windshield.

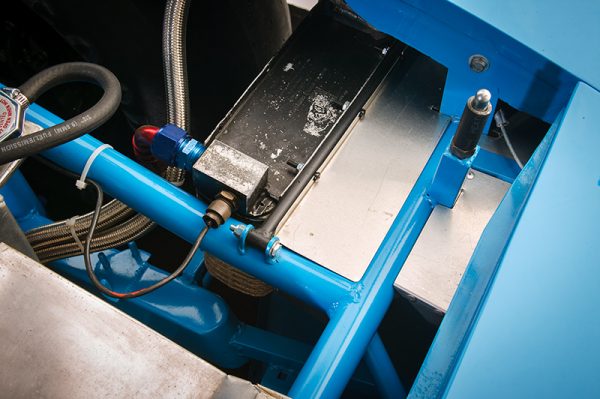

Look deep enough, and you’ll see the original Mopar frame rails. The last year of “STOCK CARS” starting out as STOCK CARS. Tubular subframe connects frame rails and roll cage. Notice the battery low on the right side for weight distribution on ovals. Fabricated control arms surround a set of dual shocks.

Who knows what secrets may hide within that huge orange intake manifold?

How bitchin’ is that! The days of bragging about cubic inches and horsepower ratings across your hood are long gone in NASCAR.

Keeping the gear oil in the differential cool is essential. Fan forces air over the oil cooler to keep temperatures in check.

Stewart Warner gauges set at angles to ensure an easy read at a glance. Everything’s right with the world when the needles point straight up. A Hurst 4 speed and a steering wheel wrapped in electrical tape for better grip. But, best of all, and maybe most telling, is an empty hole with the word “PANIC” above it.

Petty’s office chair, in all of its plaid glory.

Simple vertical side bolsters, and just a couple inches of cushion between you and one very hot floor in a 500 mile race. Fire suppression bottle, right by the drivers side, but still what looks to be a 100 miles away.

Iconic Hurst shifter. The stories it could tell......

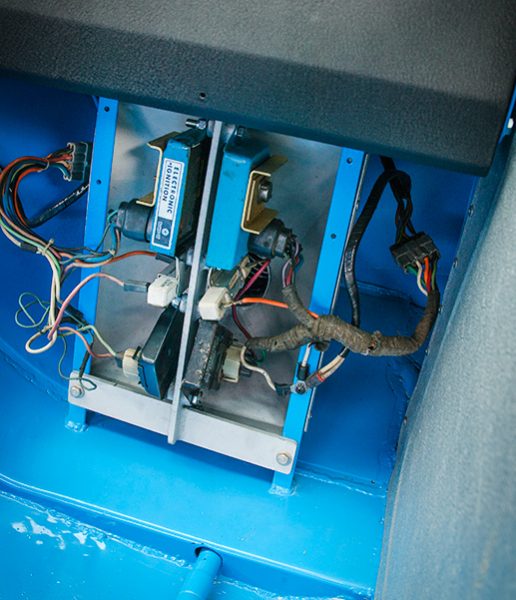

High Tech. Chrysler Electronic ignition circa 1971.

There’s a few interesting points here in the fender stack of decals. Notably, just how few there are. Today they cover fenders and parts of doors. And a local sponsor, a car dealer in North Carolina, carries the prime real estate on the rear fender.

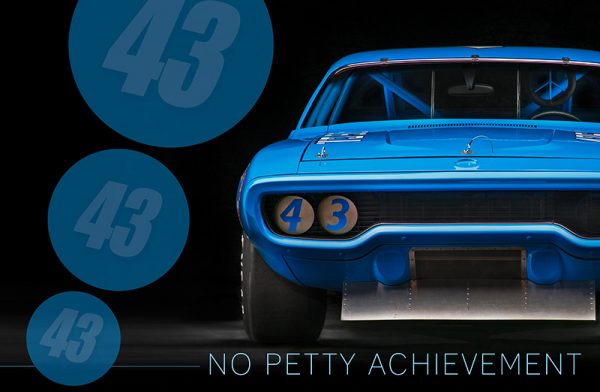

Foyt had his number 14. Earnhart is still, and always will be, remembered by the 3. But arguably, the most memorable and legendary, is that big number 43 across Petty Blue.

An interesting moment in time. Aero was still a relatively new science to racing. The Huge wings and pointed noses of the previous generation of Mopars, and droopy faced, extended nose Fords, had been outlawed by NASCAR. But smaller more subtle efforts were appearing. Chin spoilers, small by todays standards, were flat and at a fixed angle. Note the small cover over the fuel vent and the simple, somewhat crude, but effective solution for air catching the rear bumper. And when “KISS” is the best solution, a stock RED gas cap with a wedge welded on sure makes it easier to see and spin when you’re in a hurry.

For ‘71, Chrysler came out with it’s new, “fuselage” body styling on the Roadrunner and Charger. This view of the front fender shows clearly where that term comes from. The fuel cell is mounted in a basically stock trunk floor. And now common in hot rods, and resto-mods, notice the “tubbed” rear fender wells.